Delving into the history of babies during birth

Nathalie Sage-Pranchère is a historian and CNRS researcher at the SPHERE laboratory. She was one of the speakers on the round table at 7th Biomedical Rendez-vous at UTC. Her research focuses on the social history of healthcare in the contemporary era, with a particular emphasis on the history of perinatal care, foetal and neonatal illnesses and, more broadly, the history of the healthcare professions. Let the readers appreciate meeting her!

The Biomedical Rendez-vous at UTC brings together key players in the development of medical practices, placing at the heart of the debate the aim of biomedical engineering: to improve the way patients deal with and experience diseases, by facilitating medical action in all its forms (diagnosis, screening, treatment, recovery). Nathalie Sage-Pranchère was therefore keen to be present. Her forthcoming book will look at the history of rhesus incompatibility disease, from the first observations in the late 19th Century to an understanding of the origin of the disease with the discovery of the rhesus factor in the early 1940s. ‘This exploration of the past allows us to take a fresh look at periods and contexts that defy our contemporary evidence (asepsis is a recent ‘invention’ ; maternity wards were for a long time places of assistance and antechambers of abandonment, etc.). It sheds light on the roots of certain current practices (the strict supervision of pregnancies) or certain professional positions (the medical status of midwives)’, explains the researcher, whose assiduous attendance at paediatric surgical services in childhood fuelled a deep-seated curiosity for the medical world. ‘What’s more, my discovery of the contemporary issues surrounding perinatal care, the management of female reproductive health and child health has reinforced this interest. Today, my research inevitably brings me face to face with the question of the link between technology and the human beings, whether in my objects of study or in those I use to produce them and make them known. The way I look at it is through a use-based approach, taking care never to see technology as an end in itself.

Humanising medicine and patient safety

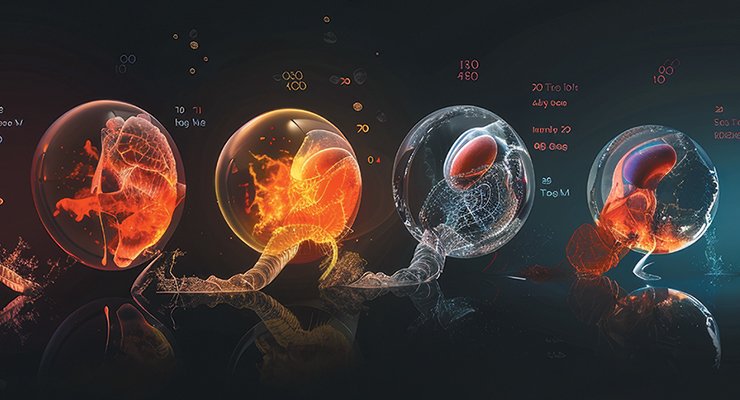

The history of the newborn is marked by a major turning point in the second half of the 18th Century, when policies began to be implemented throughout Europe to improve birth conditions and reduce maternal and neonatal mortality, primarily through the training of midwives. The first resuscitation practices for newborn babies were developed at the same time. ‘The physical survival of the newborn became as precious as its spiritual survival, which had previously been central in almost unanimously Christian societies. This development was at the root of all the changes that followed: care for premature babies from the 1880s onwards with the invention of the incubator, the development of maternal and child protection, the emergence of cuttingedge foetal medicine with the development of increasingly sophisticated imaging techniques from the 1970s-1980s, and so on. ‘According to the historian, progress that is still possible in terms of infant mortality is certainly based on technical advances, but above all on public policies that pay attention to the living and working conditions of pregnant women, as well as to the quality and accessibility of medical resources for monitoring pregnancy and childbirth. ‘All this implies a sufficient number of healthcare professionals, substantial investment in healthcare institutions, and a non-accounting approach to medical support. The humanisation of medicine, which is absolutely compatible with patient safety, also requires healthcare professionals to receive more training in the human and social sciences, so that they can approach patients as people rather than as potential disease sites.

KD